Shannon Appelcline is an ENNIE award winning historian of tabletop roleplaying games. He’s authored books on RPGs of all kinds, from the star spanning Sci-Fi epic Traveller, to the eldritch Lovecraftian horror game Call of Cthulu. His latest project documents the early history of Dungeons and Dragons. Appelcline has already written several books on D&D, he really knows his Beholders from his Bulettes. Today, he’ll be giving Wargamer the inside scoop on his new series, Designers and Dragons: Origins.

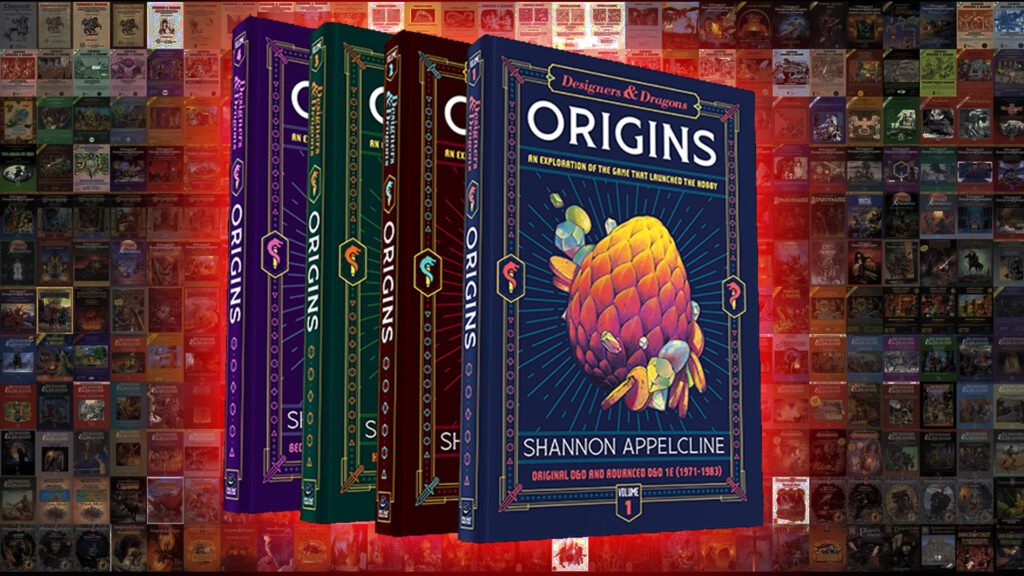

Appelcline is currently crowdfunding his four volume in cooperation with Evil Hat Productions (the publishers of Fate, Blades In The Dark, and Monster of the Week). The books detail the earliest days of D&D, when it was closer to a War Game than an immersive roleplaying experience.

The Designers and Dragons: Origins crowdfunding campaign is currently live. It launched on the 20th October, and is set to end on the 20th November. It has currently raised over $100,000 (£75,000) exceeding its initial goal of £50,000 (£37,000). It’s estimated to ship in July 2026.

We caught up with him to discuss the project, as well as his thoughts on the tabletop gaming industry, and what it’s like to document the history of his most beloved hobby. Read on for our full discussion, lightly edited for clarity.

Content Warning: This interview discuses the origins of Dungeons and Dragons. Some of D&D’s early modules appropriated Indigenous cultures and employed harmful stereotypes. Some readers may find this offensive or distressing.

Wargamer: To start us off, would you be able to talk a bit about yourself? How did you end up becoming a tabletop gaming historian?

Shannon Appelcline: I’ve been gaming since I was 10 or so, when my dad got me a copy of Dungeons and Dragons and ran me through my first dungeon. I started writing history around 2005, I think.

I had just gotten back from Gen Con, and I was very excited, so I decided to start writing a software package for RPG.net to allow people to index roleplaying games. I had the book Heroic Worlds by Lawrence Schick in my mind. It was put out in 1991, and it was a catalogue of pretty much every role playing game up through 89 or 90. I thought there are clearly a lot more now, but we could do it online.

I wrote an index program for for rpg.net (which is still there) and I started entering my collection in. Part way through, I was entering a line called Imperium Games, who took over the design of Traveller after Game Designers’ Workshop went under. I said “wow, there’s products that came out after I stopped buying it, and then the company went out of business – so I wonder what happened there?”.

So I started looking into it. I wrote about Chaosium and Wizards of the Coast, and I started writing pretty organically. That’s because I wanted to index it – because of Heroic Worlds – and because I wanted to produce content for RPG.net. The surprise was that people were really interested in it, so I kept doing more.

You mentioned that you started playing D&D when you were 10 years old with your dad. How did it evolve from there, what other RPGs did you play?

I moved into AD&D (Advanced Dungeons and Dragons) quickly, as everyone did in the era. People mixed together AD&D and OD&D (Original Dungeons and Dragons) pretty freely, not really understanding the difference between them.

One of my other very early games was Traveller. My aunt, who knew I was interested in roleplaying games, got that for me cold. It was a wonderful game, and a wonderful gift. It allows a lot of solo play. Mark Miller, the designer, has said that’s something he did deliberately. It came out in 1977, and the roleplaying fandom was a lot more scattered at the time. There was a lot less chance that you would have someone nearby. Even though I had roleplaying groups, on my own I made planets, ships and all that fun stuff.

I started playing Champions in junior high. I played that every day at recess and at lunch. We had 15 minutes in the beginning of the day and 30 minutes in the middle, and somehow that was enough.

As I moved into high school, some of my group were very into military things, so we played Twilight 2000 and Phoenix Command – which had a very complex system where you had to make many rolls to determine where each individual bullet would land. One of my friends got James Bond 007, which was a really neat game, it had all kinds of cool things in the boxes like clues, that were printed pamphlets with ripped out pages.

It was really when I went to college that my roleplaying tastes evolved more. I played Ars Magica there, which was much more story-oriented than anything I had ever done.

I’m noticing lots of Sci-Fi and spies.

Spies were just so much more popular in the eighties. It was part of the time.

Do you think we’ll ever get a spy game resurgence, or has that era passed?

I think it’s passed.

So let’s talk about the project. What would be the elevator pitch for Designers and Dragons: Origins?

It’s a collection of 300 product histories, each of which looks at a classic D&D rulebook or supplement and talks about its history, and what it introduced to the hobby.

What are some of the highlights of this period, what are the more interesting stories that you’ve drawn out?

It starts off very interesting. In 1974 TSR (Tactical Studies Rules) comes out with Dungeons and Dragons, and they don’t have any idea what to do with it. So you see them trying to do some rulebooks. Since they’re coming out of the wargaming community, they understand rules books. They just can’t even believe that people might want their help in producing the adventures they’re going to play.

Eventually, they decide that people are asking for help, so they put out Dungeon Geomorphs, and Monster and Treasure Assortments. These were just random tables and randomly generated dungeons. This wasn’t quite what people wanted, but it was what the designers felt comfortable doing because they didn’t want to undercut the creativity of the players, because they saw that as a lot of fun.

Finally 1978 rolls around, and they say ‘okay, we’ll do adventures’, and then adventures become 90% of their production for the next decade.

Even though the books are focused on products, I try to talk as much as I can about the people involved. The deeper and deeper I’ve gotten into the books, the more I try to tell the stories of the designers. There were slightly more than 80 designers involved in the 320 products here. So every one of them I try to give a little mini history.

Who are some of the designers you talk about? Has anyone left a contribution that has maybe not been noted?

I think many people won’t know most of the 80 designers. Robert Kuntz was this kid that played in Gary Gygax’s games. He eventually took over running part of Greyhawk Castle so that Gary could play more, and run TSR more. His contributions are kind of heavy in the early industry. He came in, he worked a bit, then he left and came back, and then he left again.

I trace three different times in the books where he arrives and disappears. There were often interesting things that he contributed along the way. He had his own setting called Kalibruhn that later got incorporated into Greyhawk. I think a lot of people won’t know that whole story, or about his involvement.

You said he was a kid, how old was he?

I think maybe he was in high school when he started playing with Gary. He started working for TSR more regularly by 1974 or 75. He and his brother Terry were two of the first dozen or so employees. He was around eighteen by then, but he was a teenager, not quite an adult, when he started playing with Gary and his miniatures group.

Some of the supplements that you cover in this book, like The Rogue’s Gallery, talk about the characters that were played by D&D designers. What sort of PCs did they create? Are there any standouts?

I think one of the most interesting things about the early characters is that so many of them were brought in through play. Bigby (of Bigby’s Hand fame) started off as a villain, and then he became a henchman that helped the player characters, and then he became a full character in his own right. Lots of henchmen and hirelings evolved like that.

Thinking about The Rogue’s Gallery itself, there’s a lizardman in there, despite the fact that was against the rules of Advanced Dungeons and Dragons. They had a non-official player character race in one of the books, which I think speaks to their originality.

One of the other things I love about a lot of the early characters is how many of them, especially in the Blackmoor setting, just shared the same name as the player who was playing them. There was a really narrow line between the fantasy and the reality. Sometimes they just wanted to play as themselves in a fantasy realm.

Are there any parts of this history that are uncomfortable? Do any of the supplements have problematic elements?

There’s certainly a lot that we would now view through a different lens. One that really struck me was called Drums on Fire Mountain. It’s an island adventure with a nautical theme. The Orcs on the cover are made out like Polynesians, they have all of the characteristics of if you were going to draw a stereotypical Polynesian. The campaign is equating them with a real race and it’s very problematic.

I’ve never seen any indication that anyone involved with any of these products was racist, but they certainly did things that were harmful.

The other one that really gets me is the Orcs of Thar. When Bruce Heard put together the Orcs of Thar, he wanted to make Orcs that were satires of the cultures of the setting he was using, “The Known World”. He was going for dumb humor, but problems arose because the cultures of The Known World were very solidly based on real world cultures.

Some of these cultures are based on things like Carolingian France, so that’s no biggie. One of them was based on Native Americans, and you ended up with Orcs that were parodying Native Americans in very harmful ways. It was really punching down, and not nicely so.

There are certainly things here and there, and those are the ones that I found the most problematic. They would not be published like that today.

Both of those examples were by Europeans. Drums on Fire Mountain had a British Illustrator and Bruce Heard was French. I have a suspicion that they lacked cultural understanding.

For this book we had a sensitivity expert, James Mendez Hodez, who came in and helped us through. It was a really interesting experience. He was able to explain how certain things were harmful, and how stereotypes can be harmful. I was then able to explain it in the books.

It never struck me that there was anything that the designers and artists were doing intentionally, but that’s the problem with a lot of systemic racism. None of us understand what we’re doing, but it creates impact downstream and hurts people who are vulnerable.

How would you say the way that people play D&D has changed since the period that you cover in the books? Not so much in terms of how the rules have changed, but in terms of what a D&D session looks like now, versus what it would have looked like in those earlier days.

I think the thing I always find the most amazing about descriptions of really early D&D sessions is the quantity of players. I have seen more than one description of 20 people playing at a table.

I have played in a game like that – one of my high school Rune Quest games had a max of 15 or 20 players over one summer. We had to sit at two different tables, it didn’t work. I think with OD&D it might have worked a little better, since it was so much closer to its wargaming roots.

You see descriptions of a ‘caller’ in some of the original rulebooks: someone that collects what the players and doing and transmits it on to the Dungeon Master. Other people have written very well about some of the differences in old-school play.

The other thing that’s very different is how much the original games were site-based. That’s not my term, I’ve borrowed it from others, but the oldest games weren’t thinking about story. You might have a bit of backstory about what the dungeon is, perhaps there’s a bit of story embedded in what’s in the rooms and what you might find, but they were primarily about interacting with and exploring an environment.

Two major changes come in 1983 and 1984. The first of those are the UK series of adventures from TSR UK. The TSR UK adventure starts off with a kind of site based adventure, but it’s very Shakespearian. It’s called Beyond the Crystal Cave, and it’s Romeo and Juliet in a magical garden. After that, The Sentinel and the Gauntlet is about two artifacts that have been battling throughout history. The first time I read the description, I thought it must’ve been written by someone who had just finished reading some Tolkien.

When 1984 comes along Tracy Hickman, and a number of other people, put out Dragonlance. Dragonlance has a big story that’s divided into three acts. A lot of old school players feel like this is the beginning of the end for classic era D&D because it changes everything. On the other hand, it still has a lot of site focus. There was this magnificent map of the lost city of Xak Tsaroth. It was site-based still, but there were things that pushed you onto the story here and there.

Overall those were the two biggest changes: the size of groups, and the change from a site focus to a narrative focus. One of the things that I try to do in Designers and Dragons: Origins is that I always talk about what the products introduced. Things like the first appearances of different NPCs and monsters. You can see the focus change very clearly through the adventures.

How do you view the role of D&D in the modern TTRPG ecosystem? It’s easily the biggest fish, but how does that impact everything else around it?

If you had asked me about D&D’s impact in the 80s and the 70s, I would tell you that much of the rest of the industry is a response to Dungeons & Dragons. I think that’s true historically. Nowadays, I don’t think that’s so true. Certainly, there is still a portion of the industry that is a response to D&D. When someone puts out a new fantasy roleplaying game, they’re mostly responding to Dungeons and Dragons.

A lot of innovation occurred in the indie section of the industry starting around the start of the 21st century – games like Sorcerer and Dogs in the Vineyard. Due to the fact that it has gotten a lot easier to publish both digitally and professionally, there are now a lot more people who aren’t afraid just to go their own way and design their own game.

I think there’s a fairly rich ecosystem of games that don’t care about Dungeons and Dragons any more. Perhaps they would like to attract Dungeons and Dragons players, but they don’t have to. I would say, in some ways, that Dungeons and Dragons is less relevant to the industry 1761706779 than it was at any other time.

That doesn’t mean that it’s not the biggest dog, it still is, I wouldn’t be shocked if it’s still 80 or 90 percent of the industry. If you’re in that other 10 or 20 percent, maybe you’re responding to it, but just as often you don’t care.

One of the most interesting things I’ve found is that it feels like Dungeons & Dragons is responding to the rest of the industry more than it ever has, as well. Things like advantage and disadvantage rolls in 5th edition. That type of dramatic escalation, that’s something much more common in the more freeform industry. There’s much more of an emphasis now on storytelling than in any other period.

It might be that is just the designers; there’s more cross pollination of designers than ever before. If Wizards hires someone, they have likely worked somewhere else before. That’s very different from the era when TSR were bringing in all of the original designers.

One final question. Would you be able to tell me about your favorite TTRPG moment? Something that made you think about how great the hobby is?

I love playing tricksters, it’s one of my favorite types of characters. One of my favorite long term games that I played was a Rune Quest game. One of my friends was playing a very honorable character. He had accepted one of our enemies’ surrender, even though we weren’t really taking prisoners, but he did because he was honorable. So my trickster character ran up and killed the person he had just accepted this honorable surrender from. He was furious, and yet did not know what to do about it.

I’ve also had a lot of fun running sessions over the years. I like running puzzle games. I remember, in one Pendragon game I ran, there was a puzzle where there were a whole bunch of different clearings and glades, and different things that could be picked up. You could move things from one glade to another, and they would help out. You needed to figure out how they all fit together. I think it was called The Adventure of the Holy Sword.

My players were running around and they kept running to different places and things reset, and they didn’t know what to do. Eventually they threw up their hands and were in utter despair. That was a joyous moment. Whenever you’re a Game Master and you can get your players to utterly despair, especially if they knuckle down and figure it out afterwards, it’s just great.

For more Dungeons and Dragons content, you can check out our D&D Release schedule. We also have guides on all of the playable classes, and all of the playable races. Plus, there’s always a good discussion rumbling about Dungeons and/or Dragons over on the Wargamer Discord server.